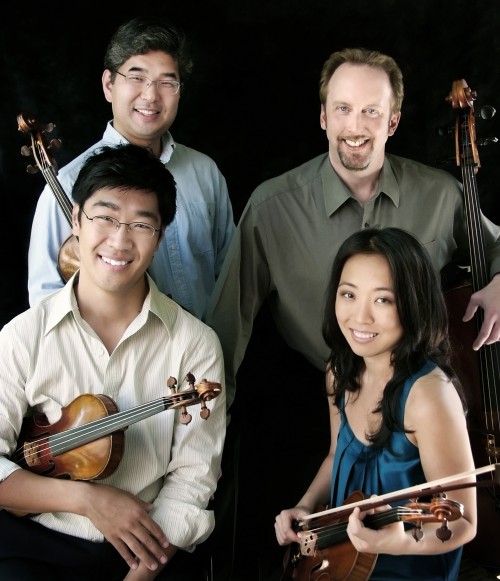

This afternoon at Smith College (short notice, I know), the Johannes String Quartet, along with John Dalley and Peter Wiley from the Guarneri Quartet will perform works by Esa-Pekka Salonen, Felix Mendelssohn and Johannes Brahms. The concert, co-presented by Music In Deerfield, starts at 4:00, preceded by “Concert Conversations” at 3:00, and will take place at Sweeney Concert Hall, Sage Hall, Smith College, Northampton. Tickets will be available at the door. Click here for further information.

Here’s what I wrote for the program booklet:

Elsewhere in today’s printed program, you’ll find information about the first work on today’s concert, Esa-Pekka Salonen’s “Homunculus.” To say the least, Salonen has an unusual and colorful explanation for his music, one which would no doubt effect how you hear the work if you read the program note first. But don’t start reading it yet. I’ll explain why later.

So how about today’s other works, by Mendelssohn and Brahms? How are they to be explained?

They can’t be, really. Sure, we know a few salient fact about them, such as that Felix Mendelssohn composed his Quartet in F Minor as an homage to his sister Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel (also a talented composer), to whom he was extraordinary close. And that it was to be Mendelssohn’s last major work, his own life to end prematurely in the year of the quartet’s composition, 1847. About the Brahms, other than its dates (1864-65), there’s even less to know. So, to rephrase the question, how are these works to be heard?

As music, that’s how. Among Romantic composers, Mendelssohn and Brahms were the foremost exponents of “absolute” music – must that tells no story, paints no picture, isn’t about anything. While the other, more descriptive kind, usually called “program” music, is fun, “absolute” music represents the greatest tradition of classical instrumental composition. Even “program” works (e.g., today’s Salonen) have to stand by themselves, not depending on their story, if they are to have any staying power.

Let me then suggest an alternate method of hearing “Homunculus,” one which of course you can select or reject as you prefer. Try hearing it first, before reading Salonen’s program note. Then, after it’s done, go ahead and read up. You might find that this way, you’ll be more absorbed in the music and less distracted by the story.

P.S. Here’s Salonen’s note on his work:

I wanted to compose a piece that would be very compact in form and duration, but still contain many different characters and textures. In other words, a little piece that behaves like a big piece.

I have long been fascinated (and amused) by the arcane spermists’ theory, who held the belief that the sperm was in fact a “little man” (homunculus) that was placed inside a woman for growth into a child. This seemed to them to neatly explain many of the mysteries of conception. It was later pointed out that if the sperm was a homunculus, identical in all but size to an adult, then the homunculus may have sperm of its own. This led to a reductio ad absurdum, with an endless chain of homunculi. This was not necessarily considered by spermists a fatal objection however, as it neatly explained how it was that “in Adam” all had sinned: the whole of humanity was already contained in his loins.

I decided to call my piece Homunculus despite the obvious weaknesses of the spermists’ thinking, as I find the idea of a perfect little man strangely moving.